COVID-19 Inspires New Course on Plague and Apocalypse Fiction

One night, as social distancing became our new normal, Mary Holland, professor of English, struggled with a bout of insomnia. Rather than counting an endless procession of fence-jumping sheep, Holland took a dystopian detour, imagining a blindness epidemic and the Black Death, zombies roaming New York City streets, and a father and son navigating a desolate landscape, “each the other’s world entire.”

One night, as social distancing became our new normal, Mary Holland, professor of English, struggled with a bout of insomnia. Rather than counting an endless procession of fence-jumping sheep, Holland took a dystopian detour, imagining a blindness epidemic and the Black Death, zombies roaming New York City streets, and a father and son navigating a desolate landscape, “each the other’s world entire.”

By dawn, Holland had drafted a syllabus for the fall 2020 graduate course, “Plague and Apocalypse in Contemporary Fiction.” Course readings challenge our sense of dominion over our increasingly unpredictable physical environment and remind us of the centrality of storytelling in chronicling and understanding the human experience.

Holland believes that apocalyptic fiction now constitutes a sub-genre in contemporary literature, with an ever-growing list of titles and plots that eerily parallel our current experience with the COVID-19 pandemic.

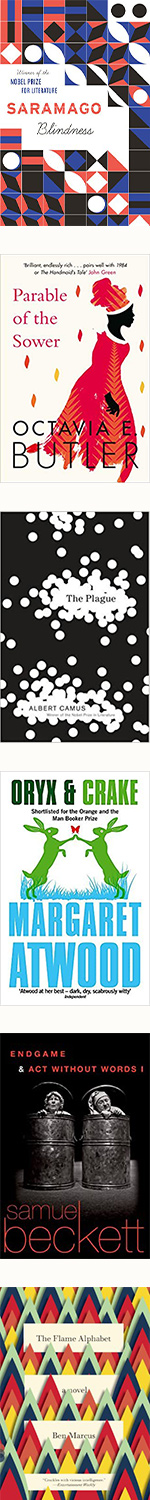

Proposed texts include Albert Camus’ The Plague (1947) and Samuel Beckett’s Endgame (1957), as well as the more recent novels Parable of the Sower (1993), Blindness (1995), Zone One (2001), Oryx and Crake (2003), Cloud Atlas (2004), The Road (2006) and The Flame Alphabet (2012).

“While many of these novels use plague or apocalypse to meditate on the human condition in timeless ways…many of them actually do hit frighteningly close to home by imagining aspects of our pandemic lives in ways that feel prescient,” said Holland, noting versions of social distancing, the wearing of masks, family relationships strained under quarantine, hoarding, grocery store trips fraught with peril, and social inequalities that determine those who suffer and those who are spared.

Though existential angst is a common feature of the novels, Holland found an interesting twist in Colson Whitehead’s Zone One, a fresh take on zombie fiction. The novel caused Holland to reflect on the ways in which the repetitive routines of modern living render people “always-already zombies.”

“My favorite detail in the novel that communicates our pre-zombieness is the ‘stragglers,’ or the one percent of zombies who do not become overwhelmed by rabid rage but instead get stuck in some place that had meant something to them in life, running through the same repetitive motions for all eternity,” said Holland. “It is impossible not to imagine the straggler version of me sitting here at my desk tapping away at this keyboard, which is what I spend an enormous portion of my time doing, especially in recent weeks.”

The course will challenge students to consider the lessons offered by apocalyptic narratives in reflecting on their own experiences living in uncertain and fearful times. The novels all share what Holland describes as a “sense of global crisis as a mechanism for vision,” one that helps us to evaluate our priorities, illusions and sense of shared humanity.

Will students’ experiences resemble the plots of The Plague and Parable of the Sower, which view tragedies as bringing forth our better angels, or Blindness, which imagines the triumph of humanity’s basest instincts, or some combination of both?

For Holland, simply taking up the questions raised by the novels is a worthy exercise in self-reflection: “How will this pandemic, and the extremity of the experience, change our lives? How will we respond to it, individually and as a community? How can I be my best self not despite the crisis but because of it? For what parts of my banal life can I discover renewed and lasting gratitude? How might I use my anxiety over my and others’ mortality to press me to see what’s truly important? How might I hold on to these discoveries beyond the urgency of the crisis itself?”

Reading apocalyptic novels will also bring into sharper focus the importance of language in documenting tragic and unpredictable events, and hopefully, learning from them essential lessons.

As Holland notes, the novels employ a wide variety of genres or technologies of writing, from diary keeping to oral histories to unusual forms of direct address. “Even in The Road, which is ostensibly told using a mixture of third- and first-person point of view, the father often speaks to some listener and imagines ‘scribing’ his experience. That is, despite the destruction of every kind of technology we consider necessary for telling and disseminating history and our stories, these novels emphasize the importance of doing just that, using any ‘technology’ available to us,” noted Holland.

“So I imagine that one thing we will think about as we read all of these novels together is that—despite recent arguments to the contrary—reading, writing, and teaching about stories, at every level, are crucial to our continued humanity.”