A Q&A Session with Anna Gjika

In a rapidly evolving digital landscape, teenagers, parents, and our society at-large are struggling to navigate a growing—and particularly troubling—trend: image-based sexual violence, which broadly refers to the digital creation and distribution of nonconsensual intimate images.

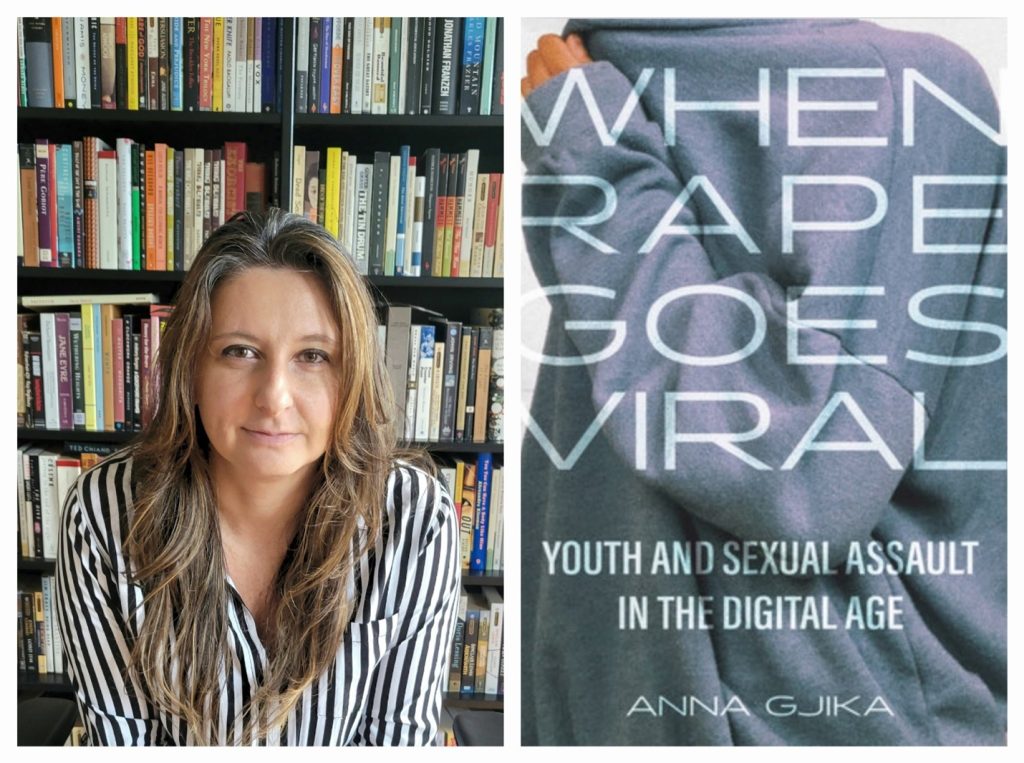

In her new book, When Rape Goes Viral: Youth and Sexual Assault in the Digital Age, Anna Gjika, assistant professor of sociology at SUNY New Paltz, confronts the taboo topic head on, bolstered by in-depth research, case studies and invaluable insight from teens, attorneys, and others.

We met up with Anna for a Q&A about her book, available at the Sojourner Truth Library on campus.

Your book began as a dissertation at the CUNY Graduate Center. Why was it important to bring your research and findings on image-based sexual abuse into the public sphere?

Some of the earliest instances of this phenomenon involved cases of teens capturing and sharing sexual assault across social media platforms, with some of the young victims committing suicide. The incidents drew heavy media attention as adults struggled to understand why teens would record themselves committing a crime, and worried about the consequences of technology for youth and their well-being. My dissertation research focused on answering these questions and fears, while also arguing for what I thought was missing in public responses to these cases at the time—a recognition of the recording and distribution of sexual assault as a new type of sexual violence.

Our understanding of and responses to digital abuse have improved in recent years, however, explanations for why individuals partake in such behavior are lacking. We are still not talking about causes, which are fundamental for prevention and harm reduction. These trends influenced my decision to turn my dissertation into a book. In it, I offer a theoretical framework for understanding the motives informing digitally abusive practices, and provide a detailed analysis of how the criminal legal system is responding.

How did you approach your conversations and dialogue with your book’s primary sources?

I organized my conversations with teens as group interviews to ensure their comfort and scaffolded the discussion to build trust. Most interviews started with general social media habits and norms, and common behaviors teens share. Then we would move on to riskier or more intimate practices, such as dating, partying, and sexting and image sharing. Toward the end, I gave participants one of the cases discussed in the book and asked them to talk about it. The teens I spoke with were incredibly honest and generous in their responses, and I learned so much from their insights.

How has the digital age impacted peoples’ perception of image-based sexual abuse?

Image-based sexual abuse is a growing problem. Women, girls, and LGBTQI+ populations are disproportionately impacted, which follows patterns of other forms of sexual violence. Many survivors find image-based abuse uniquely harmful due to the risk of images being widely shared and the difficulty of controlling their spread and digital afterlife. There have been important social and legal developments toward recognizing the problem, and social media platforms have been a key site for improving awareness and fostering discussion. What I want people to understand, however, is that in practice, institutional responses to image-based abuse are messy and uneven.

As a new author, what did you find most challenging throughout the publication process?

It’s an emerging field and there were so many new developments while writing, editing, and waiting for the book to be published, that I kept worrying about missing a new study or a key piece of legislation. Coming to terms with the ongoing nature of research is important.

How does it feel to have your book recognized by the American Sociological Association as the winner of its ‘2024 Distinguished Book Award’ within its Sex & Gender category?

It is an honor to win this award. I wrote When Rape Goes Viral to offer a gendered analysis of image-based abuse that I think is missing in the field, and to provide a critical assessment of the ramifications of digital technologies for the problem of sexual violence. It’s validating and rewarding to have this research recognized for its contributions to the Sociology of Sex and Gender.

What’s next for you? Are you working on any other special projects?

One thing young people in my research noted about social media is the ways they facilitate privacy violations, like snooping, through their features, which can slip into nonconsensual and intrusive behaviors. I’m investigating how the design of social media platforms contributes to invasive surveillance practices among romantic partners, and what this means for image-based abuse.