“Boy Erased” Author Practices Radical Compassion

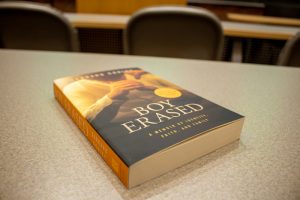

Subjected to an intense, two-week residential counseling program that merged the 12-step meeting format with fundamentalist Christian teachings designed to “pray the gay away,” “Boy Erased” author Garrard Conley emerged with a compelling personal story that has fascinated readers and inspired an acclaimed film adaptation.

In telling his story honestly and without judgment, Conley received more than critical success. He discovered the meaning of “radical compassion,” which he shared with a campus audience during a Nov. 19 lecture of the same name.

“Spoiler alert: I’m still very gay,” Conley said at the start of a free-flowing, conversational talk with a powerful thesis: stories teach us compassion, help us heal and show us that we are not alone. By sharing our stories, we can end harmful practices and repair a broken world.

“I have been converted in only one way: that is in believing that stories matter,” Conley said.

“Love is no longer unconditional”

Conley’s story begins in Milligan Ridge, Ark., where he first developed his understanding of love and compassion while a Missionary Baptist Church congregant.

During his freshman year at a Presbyterian liberal arts college, Conley spent his days studying literature and writing short stories in a moleskin notebook. Away from his close-knit hometown, Conley confided in a roommate a secret he’d held since childhood: he thought he might be gay.

In a moment that altered the course of Conley’s life, his roommate sexually assaulted him and confessed to abusing a 14-year-old boy in his youth group. When Conley confided in the campus pastor, the roommate retaliated by calling his parents, telling them that Conley lived an “openly gay” lifestyle.

Conley’s mother immediately retrieved him from school. At home, his father fumed. Just a few years earlier, he’d shaken and wept during a church service, declaring his calling to become a Missionary Baptist preacher.

He embraced a fundamentalist worldview and believed in the Bible’s literal interpretation, using passages like Leviticus 18:22, “Thou shalt not lie with mankind as with womankind: it is an abomination,” to denounce LGBTQ identities. He could not abide a gay son.

To Conley, he issued a warning: if he acted on his homosexual feelings, he would not continue his education or see his family again.

“[It was] the worst thing anyone can ever hear from a parent—that love is no longer unconditional; it’s got some very specific conditions that you don’t even think you can live up to,” Conley recalled.

Conversion Therapy

Through their church, Conley’s parents learned of a program administered by Bellevue Baptist Church in Memphis, Tenn., called Love in Action (LIA), which used conversion therapy to treat homosexuality and claimed an 80% cure rate. He enrolled in the residential program between the summer of his freshman and sophomore years.

Not strictly LGBTQ-oriented, group therapy sessions included practitioners of bestiality and pedophilia, as well as those experiencing marital problems. “We were all placed together under the common idea, which was another literal interpretation of the Bible, that we were all sinful or addicted to an aberrant behavior,” he said.

LIA staff, Conley noted, exhibited “classic cult behavior,” prohibiting members from visiting what they determined to be sinful places, including movie theaters, malls, non-Christian bookstores and “secular” restaurants. Many counselors were themselves former conversion therapy recipients who found refuge from a wicked world inside LIA’s walls.

Conley’s mother, who stayed in a nearby hotel for the program’s two-week duration, could not observe the program and received no communication about the therapy’s methods, which Conley said relied on damaging stereotypes and literal interpretations of the Bible.

We were all placed together under the common idea, which was another literal interpretation of the Bible, that we were all sinful or addicted to an aberrant behavior.

In one exercise, Conley was asked to complete a genogram, a family tree coded with “sin symbols” representing abuse, violence, murder, addiction and homosexuality. “The idea is that the sins that your fathers have committed in the past trickle down to future generations and cause other sinful behaviors,” Conley explained. “I had to put an ‘H’ [for homosexuality] beside my name because of this other stuff in the family.”

Later, counselors ordered Conley to yell at an imagined vision of his father and “tell the truth about how much you hate him,” thus enacting a gay male stereotype that Conley described as a “really bad reading of Freud.” He refused, and abruptly ended his therapy.

Conley identified a disconnect between the Bible’s teachings and LIA’s insistence that he feel something he didn’t in order to be “cured.” Conley felt sad about his relationship with his father and longed for their former closeness, but he didn’t hate him. He asked his mother to take him home.

Fearing her son’s death by suicide if he continued therapy, Conley’s mother relented, and the family didn’t speak about the experience for a decade.

“A project that involved my life”

Though Conley returned to college to study literature and joined the Peace Corps in Ukraine, he felt angry at his parents and the LIA counselors, whom he believed had prevented him from becoming the writer he was meant to be. He envied his peers who could develop their literary talents unburdened by trauma.

“I was writing those stories—they were bad stories—in my moleskin, in classrooms like this, but they would’ve become good stories in time, and I was angry that instead, I was spending all my time thinking through all this stuff,” he recalled.

In time, Conley realized that he must let go of anger to find peace. He drew strength from the lessons he’d learned from literature. He reached out to those who had harmed him, engaging in difficult conversations with his parents and counselors to find shape, pattern and meaning in his experiences.

“I began to see a project that involved my life, and I could take these raw materials that felt so shameful to me and felt so angering, and turn it into some sort of message,” Conley said. “I learned that from literature, from reading other great writers and from being in classes where good literature did not reduce people into monsters, but three-dimensional characters. When I started to write this book, I thought ‘I can’t just do what I’ve been doing. I have to do the work to understand where they came from.’”

I could take these raw materials that felt so shameful to me and felt so angering, and turn it into some sort of message.

In interviewing his mother, he came to understand how her marriage at 16 and lifelong involvement in a patriarchal religion defined the limits of her autonomy. His father revealed a dark secret of his own. He’d witnessed his father bind his mother to a chair and savagely beat her. Just as his son had turned to books to heal from his trauma, Conley’s father had turned to religion.

Conley reached out to John Smid, his charismatic LIA counselor, who left the ministry after two decades and married same-sex partner Larry McQueen in 2014. He went on to found Grace Rivers, a ministry for the gay community promising “an authentic relationship with Jesus Christ,” and acknowledged the profound harm he caused during his tenure at LIA.

Though these interactions did not lead to perfect understanding and acceptance, Conley saw how those in his circle made “steps toward compassion and towards love.”

Conley’s father apologized for subjecting him to conversion therapy, and his mother, now an activist in her own right, recently received the PFLAG Flag Bearer Award, which honored her contributions to the safety and equality of LGBTQ people, their families and allies. Garrard Conley and Smid are Facebook friends.

Ending Conversion Therapy

Beyond healing his personal relationships, writing his memoir connected Conley with a larger “queer family” and spurred his activism in the fight to end conversion therapy. Conley partners with organizations like The Trevor Project, which launched the “50 Bills 50 States” campaign to protect LGBTQ youth from conversion therapy, and is a producer and creator of the podcast UnErased, which explores the history of conversion therapy in America.

A 2018 study by UCLA’s Williams Institute estimated that 698,000 LGBT adults between the ages of 18-59 had received conversion therapy in the U.S., including about 350,000 who received treatment as adolescents.

The country’s top mental health associations, including the American Psychiatric Association (APA) have denounced conversion therapy as an ineffective and detrimental treatment for homosexuality. The APA removed homosexuality from the second edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) in 1973, no longer classifying it as a mental disorder.

Conley described the move to end conversion therapy as “one of the fastest growing LGBTQ activist movements.”

The APA removed homosexuality from the second edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) in 1973, no longer classifying it as a mental disorder.

According to the National Center for Lesbian Rights, 14 states, the District of Columbia and numerous municipalities have passed legislation protecting youth from conversion therapy. A New York State bill banning conversion therapy for minors was signed into law by Gov. Andrew Cuomo on Jan. 25, 2019.

For many years, Conley felt excluded within the queer community as a conversion therapy survivor, but the recent attention given to conversion therapy stories has made him feel more connected. With the number of U.S. residents who’ve received conversion therapy now exceeding 700,000, Conley believes that sharing stories, and listening with compassion, is more urgent than ever.

“Imagine an entire city the size of Boston filled with survivors, and you can begin to understand the amount of healing that needs to take place,” he said.

—

“Radical Compassion” is the first of two events sponsored by the SUNY New Paltz Foundation and College of Liberal Arts & Sciences, thanks to the generous support of the Robert Sillins Family Foundation. The speaker series reflects the Sillins Foundation’s mission of furthering the interests of Robert Sillins by promoting a central tenant of Judaism, tikkun olam, or acts of kindness performed to perfect or repair the world.

A recording of the talk will be available for a limited time on the campus media site. To view the recording, enter the password Books2019 at the following link.